The Hardens, who are Black, were contemplative while looking at each section of the exhibit, including one that tells the story of those enslaved women. There are bundles of cotton and replicas of cotton gins and other farm equipment on short tables. Marilyn is only 65, but she remembered what it was like to work in the cotton fields during the summer.

She also recalled stories of women having babies in those same fields.

“You wouldn’t expect the farmer to come out, but a lot of times, we did have to deliver a baby if the midwife didn’t show up,” Marilyn said. “The grandparents or somebody had to deliver in the field.”

This museum is a small part of the deeper history of this area of Jackson. It’s just a few blocks over from Farish Street, which was once the Black epicenter of the city. Harmon said that it’s impossible to talk about Mississippi’s granny midwives without mentioning the Farish District.

“It’s all Black. It’s Black cultural, it’s Black historical,” Harmon said. “Farish used to be the hub of African-American physicians, pharmacies, retailers, restaurants.”

Both Marilyn and Aurelia are educators in Florida, a state that has come down hard against teaching about race or African-American history over the past year. As she looked over the midwifery exhibit, Marilyn said it is vital to seek out Black history.

“You know, they want to infuse what they teach, that other history, somebody else’s history, but they don’t want you to know your history or take a class in it,” she said.

Mary Scott, and her daughter, Virginia Ford, owned two homes on Cohea Street, which intersects Farish, and is just a short walk from where the museum currently sits. Scott, formerly enslaved, worked as a maid and owned a laundry service, while Ford was a midwife. They used their homes to care for mothers and teach women to be midwives during an era where maternal care for Black women was limited.

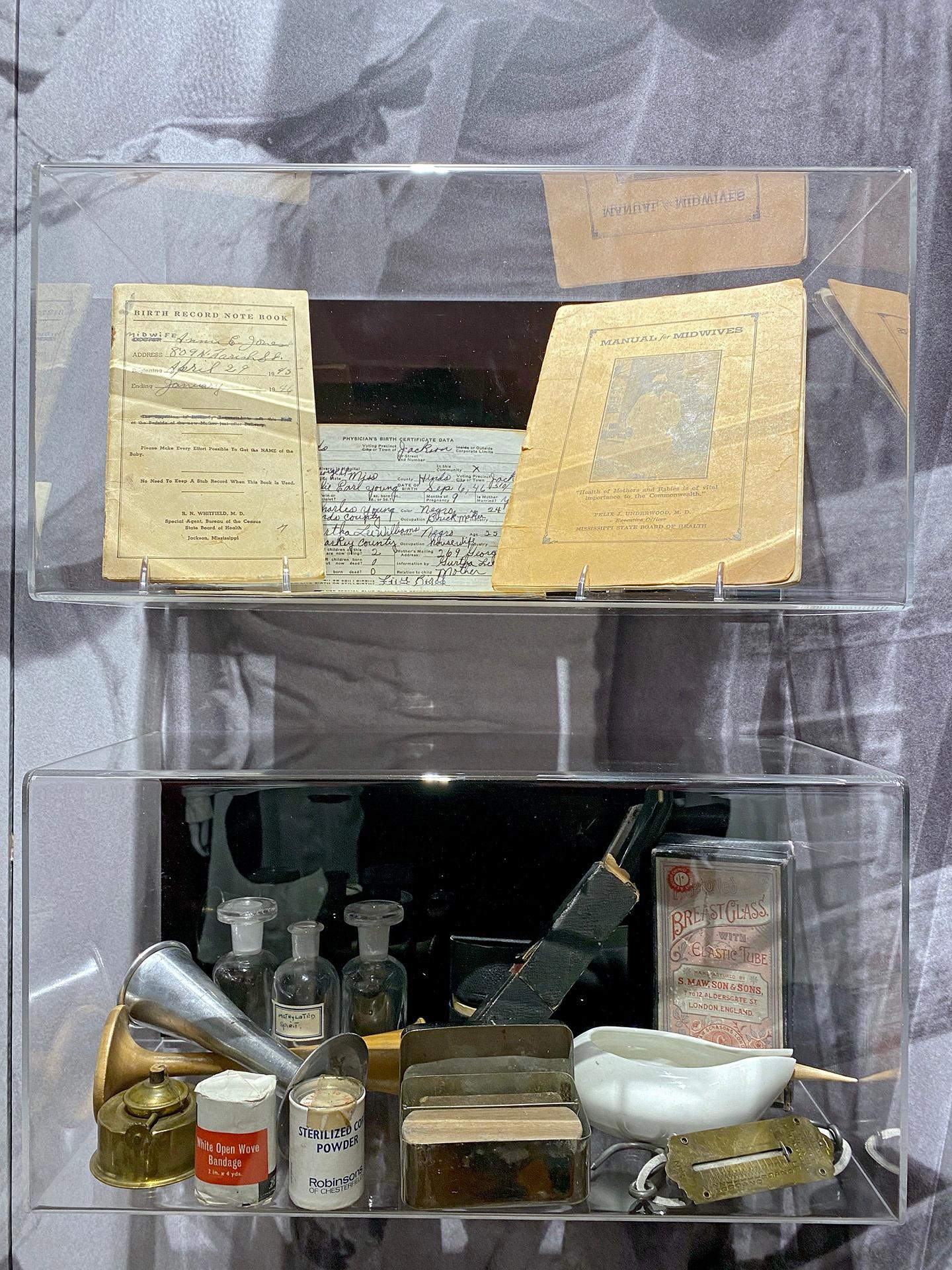

In the Jim Crow South, most hospitals would not accept Black patients. Black women, and sometimes poor white women, would call on granny midwives to deliver their babies at home. But by the mid-20th century, they were being edged out of practice.

“There are other entities that came before who find that maybe that’s an encroachment on what they had been doing — pretty much the majority white medical profession — because they started putting a lot of limitations on the midwives,” Harmon said.