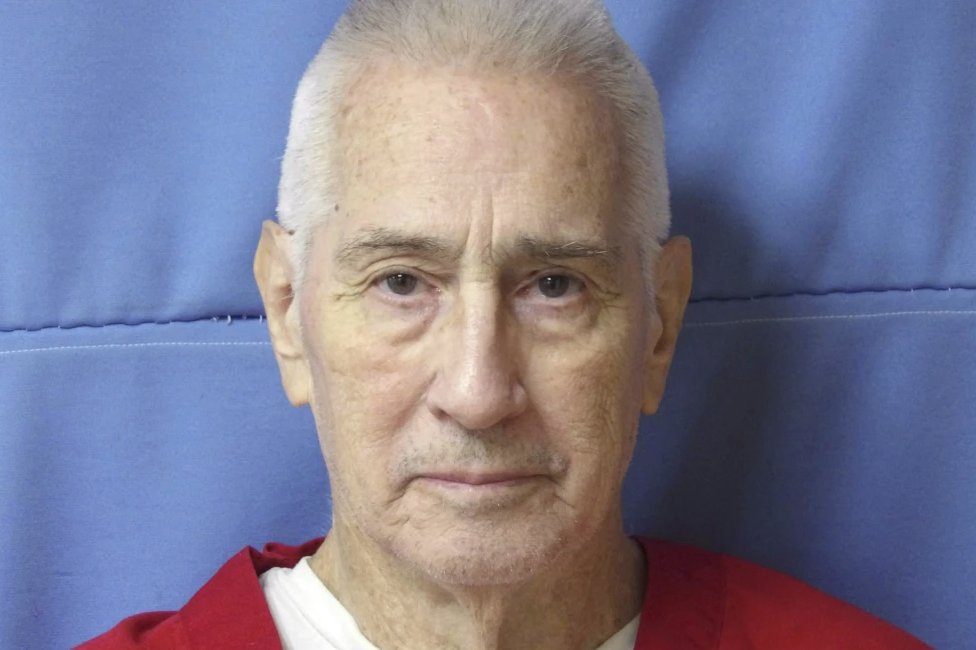

Jordan’s death came nearly 50 years after his first conviction for the kidnapping and murder of Edwina Marter in a botched ransom scheme.

Due to multiple retrials, Jordan was sentenced to death four times, and the sentence was only carried out Wednesday after the Mississippi Supreme Court, a U.S. District Court, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court and Governor Tate Reeves all declined to intervene.

When asked for his last words as the execution began at 6 p.m., Jordan said, “First, I would like to thank everyone for a humane way of doing this.” He then apologized to Marter’s family and asked for forgiveness. He also thanked his lawyers and wife, who were in attendance, and concluded with, “I love you all very much. I will see you on the other side, all of you.”

An unnamed prison official confirmed that Jordan was unconscious several minutes after he was injected with a sedative. The executioner then administered the other two drugs in the state’s lethal injection protocol: a paralytic and an agent that induces cardiac arrest. Jordan was declared dead at 6:16 p.m.

Jordan was the lead plaintiff in a federal lawsuit challenging Mississippi’s three-drug lethal injection protocol, arguing that midazolam, the sedative administered first, creates a substantial risk that a prisoner will remain sensitive to the excruciating pain caused by the other drugs. The lawsuit is ongoing.

Following the execution, Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Burl Cain said he was glad Jordan’s final hours were good ones and that his death appeared painless.

"I think the most important thing is he was remorseful," Cain said. "And the other thing was he did visit with his family. He did have the last meal with his family, as we did as well, and everything went smooth."

Several of Marter’s relatives attended the execution. Keith Degruy, Marter’s nephew, read several statements on behalf of the family. All celebrated the execution as justice being served, but bemoaned the decades-long delay.

In one statement read on behalf of Marter’s husband and their two sons, Degruy noted that the brothers are now in their fifties and still wish their mother could be a part of their lives.

“They will never have that option,” Degruy said. “Jordan took from them and he didn't deserve an option either. Although they may forgive him, it doesn't change what they missed for 49 years.”

In January 1976, Jordan traveled from Louisiana to Mississippi with the goal of kidnapping the relative of a bank employee to extract a ransom large enough to start a new life. He was referred to Charles Marter after calling Gulfport’s Gulf National Bank and asking to speak with someone about applying for a loan. Jordan then found the Marters’ home address in a telephone book and drove there, posing as an electrician and kidnapping Edwina Marter at gunpoint. He drove Edwina to a wooded area near DeSoto National Forest and shot her in the back of the head when she tried to run away. He later called Charles and demanded a $25,000 ransom but was arrested the next day in a hotel in Mobile.

Prosecutors described the murder as cold and calculated, and juries in 1976, 1977, 1983, and 1998 agreed, sentencing Jordan to death each time.

Krissy Nobile, director of the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel, has represented Jordan since 2021. She believes his constitutional rights were violated during the sentencing phase of his fourth trial because his attorneys failed to present his 33 months of combat service in Vietnam and subsequent PTSD as mitigating evidence.

“The jury was forced to make a decision for life or death based on a very, very incomplete story of who Richard Jordan is,” Nobile told MPB in an interview last week.

Franklin Rosenblatt, president of the National Institute of Military Justice and an associate professor of law at Mississippi College School of Law, says Jordan’s trial would likely have a different outcome today because of what has been learned about how wartime trauma affects the brain and the relevant case law that has emerged.

“It's not an impunity mechanism, it's not a get out of jail free card, but you do need to take into account what the veteran has been through when they are charged with regular crimes, especially those that are likely to be connected to their wartime service,” Rosenblatt said.

Rosenblatt filed Jordan’s clemency petition with Governor Reeves' office. Reeves denied the petition Tuesday evening, citing the violent and premeditated nature of Jordan’s crime.

“Justice must be done – and in Mississippi – justice will be done,” Reeves said in a statement posted to social media.

Jordan’s attorneys argue his exemplary record as an inmate is further evidence of PTSD being a major contributor to his violent crime. Nobile says that Commissioner Cain thought Jordan was such a model inmate that he allowed Jordan to get married at Parchman after he reconnected and fell in love with a childhood friend.

“I had one prison chaplain describe him as ‘a force for good’ and that is kind of what I think sums up Richard, that he really is that person on the road that everyone respects and likes,” Nobile said.

Juanitia Simmons, a retired MDOC Major who served as the supervisor for death row at Parchman for fifteen years, described Jordan as a dedicated worker who served other inmates with compassion in a personal statement supporting Jordan’s clemency request.

“I have watched hundreds of inmates come and go, but very few have grown and evolved the way Richard has,” Simmons wrote.

Marter’s family maintains that no mitigating factors could make Jordan’s execution unjust.

“Jordan's service to this country or any good he has done in prison will never make up for the moment he pulled the trigger, killing Edwina Marter,” Degruy said.

Jordan’s execution was the first conducted in Mississippi since 2022, and thirty-six of the state’s prisoners remain on death row.