Julie Ford doesn’t remember everything about her assault. She remembers being tired as she neared the end of her usual jogging route atop the Mississippi River levee in New Orleans. She remembers passing someone sitting on a bench. She remembers being “tackled like a football player.”

The rest comes in flashes. Fighting him off. Dragging herself through the dirt. Calling for help. Her husband, bystanders, and EMTs carrying her broken body to the ambulance, which couldn’t get to her on the river side of the levee.

She remembers pleading to be taken to West Jefferson Medical Center, a hospital she knew took her insurance. She didn’t know it yet, but her hip had been dislocated, nose broken and her arm broken so badly EMTs described it as being in the shape of a question mark.

Because she’d been assaulted, she remembers being told she had to be taken to a specific hospital to receive a forensic exam — sometimes called a “rape kit.” While a range of clinicians can conduct forensic exams, specialized nurses called sexual assault nurse examiners (SANE) receive rigorous training to provide trauma-informed care throughout the evidence collection and examination process. SANEs also connect survivors with resources and advocates.

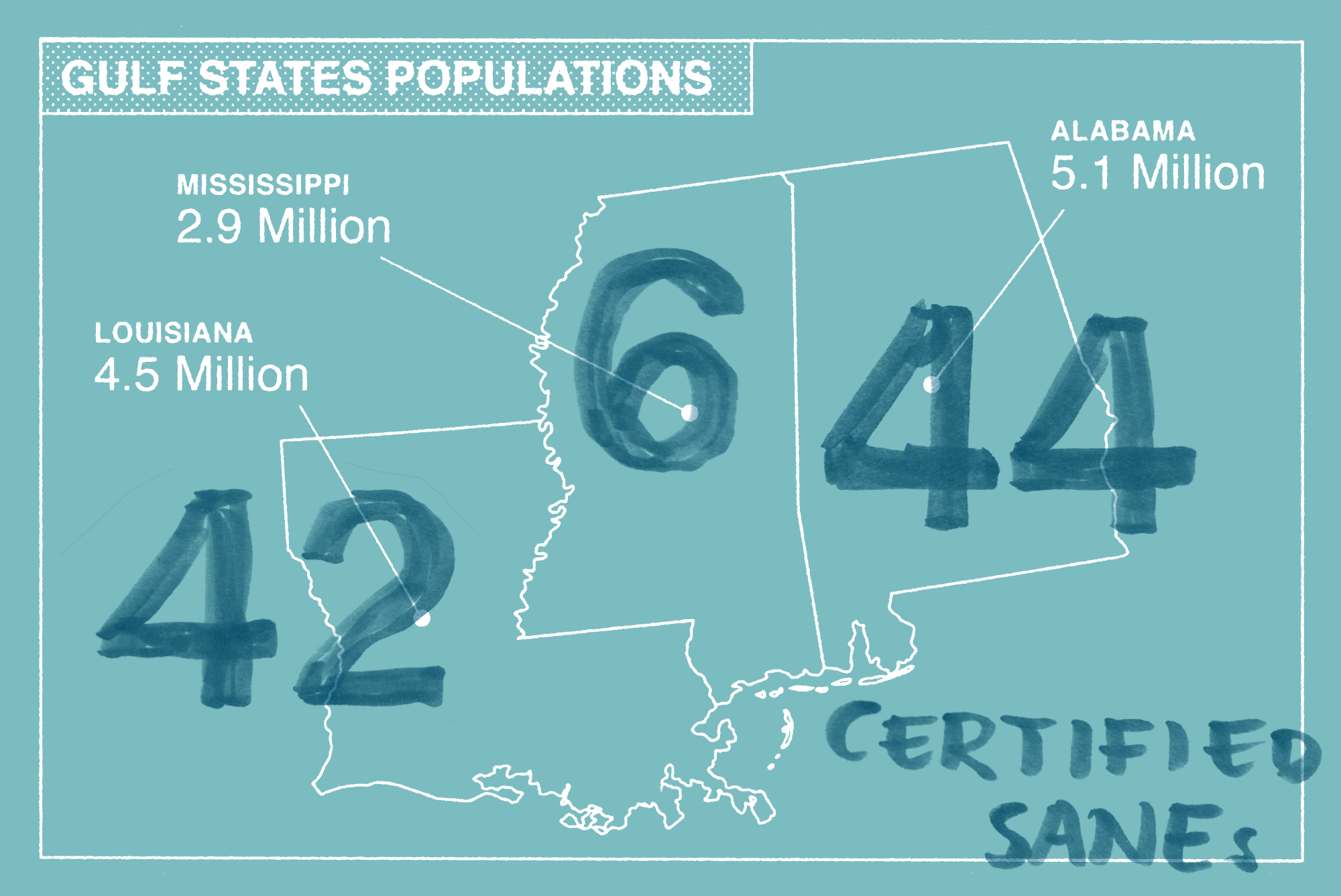

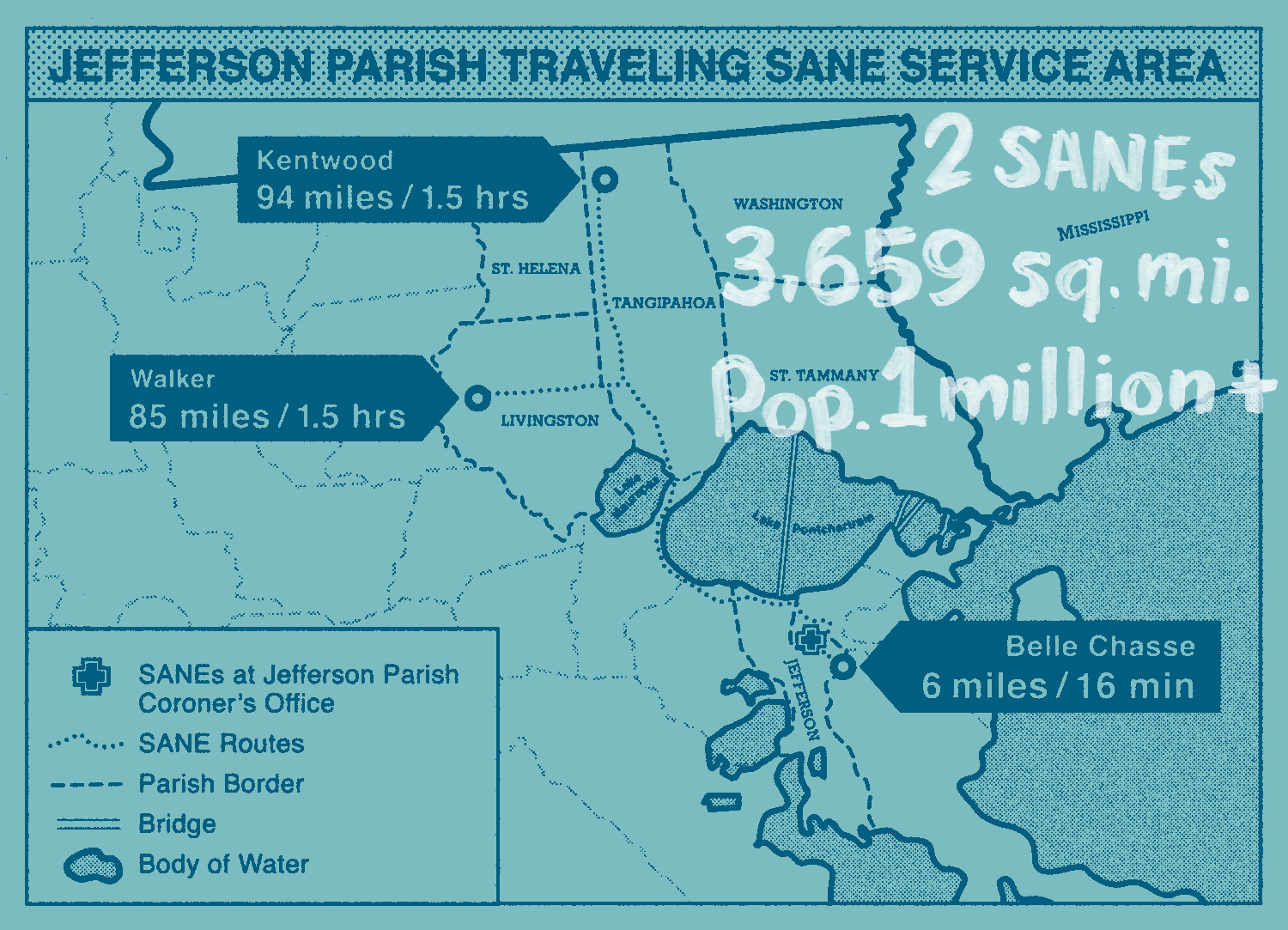

SANEs and the advocates they connect survivors with are vital for trauma-informed patient care and for bringing perpetrators of sexual assault to justice. But there is a critical shortage of SANEs across the Gulf South. According to the International Association of Forensic Nurses, a trade group that certifies SANEs, Alabama has 44 certified SANEs for the entire state. Louisiana has 42. Mississippi only has 6 — for a population of almost three million.

Where and how sexual assault patients access this resource varies greatly across the region. Although Louisiana state law requires patients have access to forensic exams in every parish, in practice not every hospital is set up to provide them. Instead, sexual assault survivors are often funneled to specific hospitals with SANEs tasked with delivering this specialized care In the New Orleans area, one of those facilities is University Medical Center, the hospital where Ford said she was taken, even though it wasn’t in her insurance network.

What followed was another blur. She said she was put in a triage area that was “very public.” There, a detective asked her the same questions she’d already answered for patrol officers. She didn’t know where her husband was or why her leg felt like it “fell off.” She said nobody would tell her what was happening.

She was confused and scared — until she was greeted by an advocate from Sexual Trauma Awareness and Response (STAR), a group that works with survivors, and a sexual assault nurse examiner.

It was the first time she felt that somebody was here to help her, she said. SANEs are trained to reach out to advocates to sit with patients like Ford while they conduct a forensic medical exam, collecting evidence that could be used in prosecution.

It would take almost a decade before Ford’s attacker would be convicted for assaulting her. Patients can’t be charged for forensic exams in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama under state law. In Louisiana, hospitals are reimbursed up to $1,600 for a forensic exam from the state’s Crime Victims Reparations fund.

But this only covers the forensic exam — not the costs related to any additional injuries. Ford said for the one night she spent in the UMC emergency department, she was charged about $20,000 for medical care related to her severe injuries, which still haven’t fully healed.

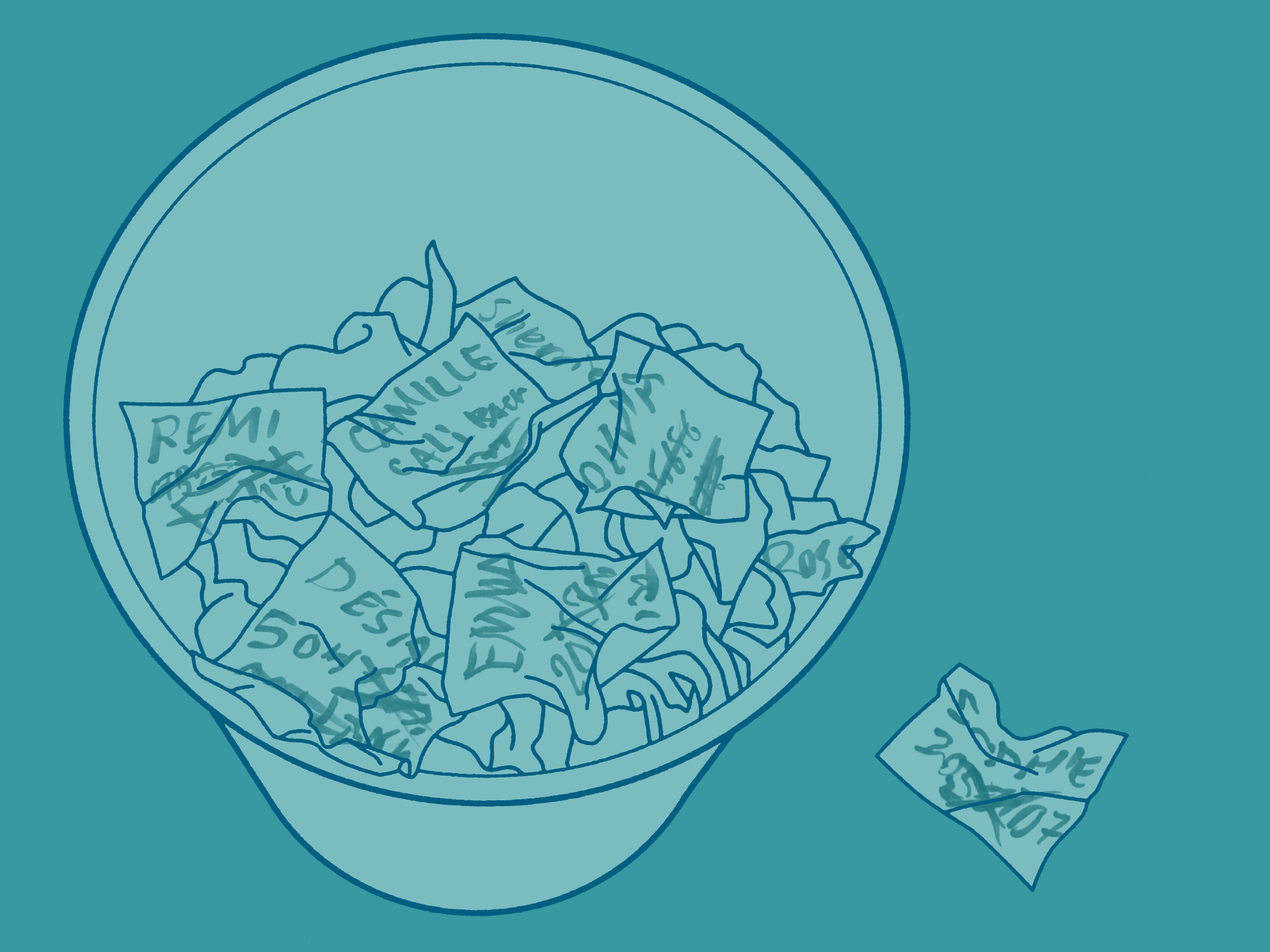

Ford said she and her husband spent months making phone calls to their insurance company, and, after tearfully recounting what happened to her over and over, eventually, they were able to get most of the bills to be considered in-network. She ended up paying more than $2,300 out of pocket for medical bills, as well as around $1,000 for the ambulance ride.

“The only thing in the system that I think worked in my entire experience was that piece, the forensic medical exam and the advocate piece,” Ford said. “I felt very lucky to have that.”

After her assault, Ford stayed in touch with her advocate from STAR and used their hotline, support groups, and legal program for guidance and support. She’s had two surgeries and years of physical therapy related to her injuries.

She’s also become an advocate for other survivors. She now volunteers with Crime Survivors NOLA, which produces a free guidebook of resources for people dealing with the aftermath of violent crime. She said the practice of sending sexual assault survivors to another facility if they want a forensic exam is a huge barrier.

“It might take a lot for that person to walk into a hospital, and you want to make it as easy as possible for them to get done what they need to get done,” Ford said.

“Just telling somebody that they have to go somewhere else, that might be the difference between that report getting taken or not getting taken.”