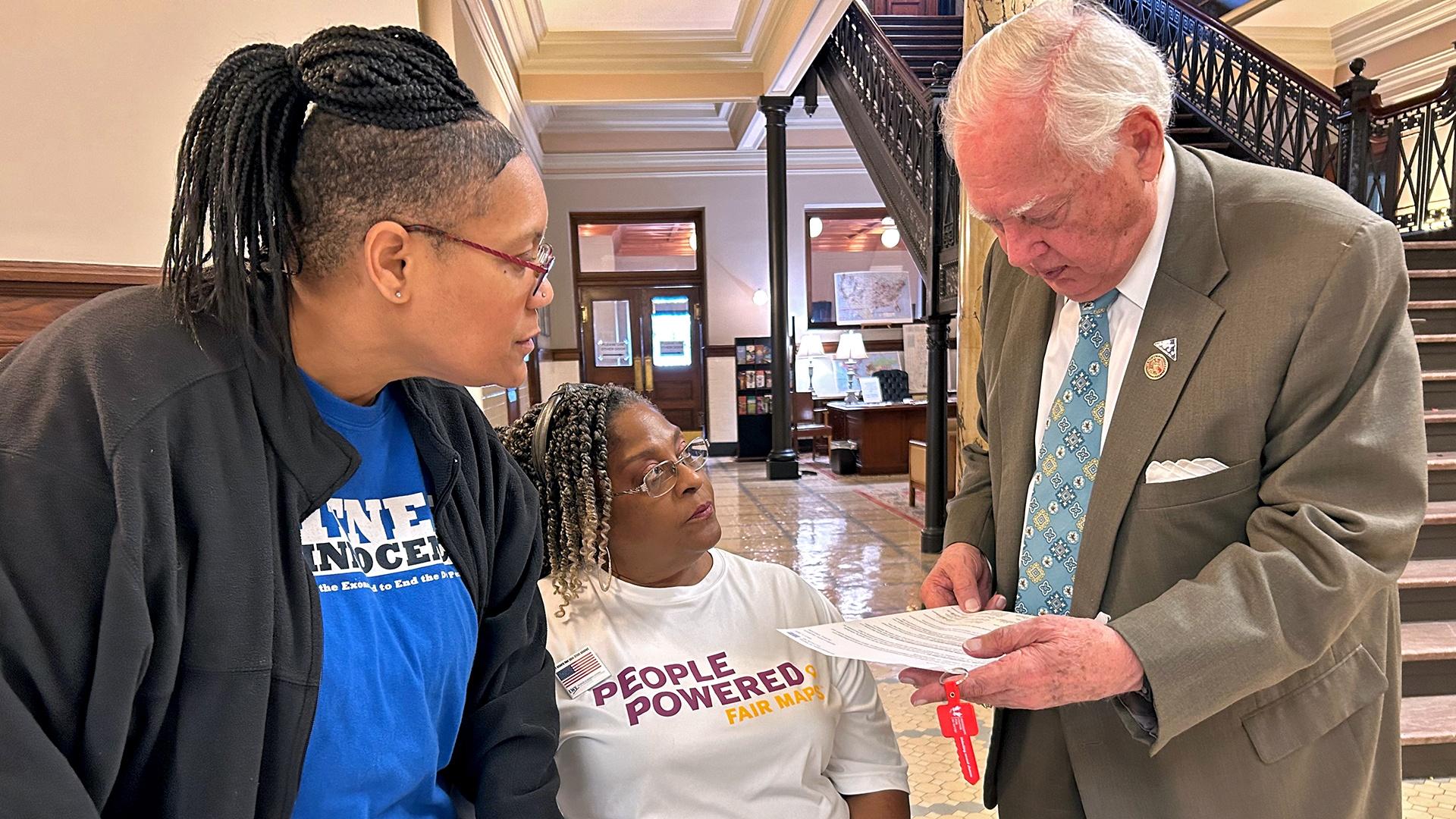

The in-person seminar in Ridgeland, Mississippi, followed online training sessions, at which participants learned more about storytelling basics and Capitol etiquette, Freeman said. It preceded a group trip to the statehouse to put new skills into action.

Such training also suggests a path to political participation beyond the ballot box for Mississippians with criminal records. Mississippi's voting rights laws for people with some convictions are among the nation's most restrictive, experts say. That's provoked court challenges.

Peg Ciraldo, co-president of the League of Women Voters of Mississippi, called the group's statehouse visit and lobby efforts “so worthwhile,” while criticizing the state's voting limitations.

"There might be people who made a mistake, who want to vote, who have a really good head on their shoulders — and we want them voting," Ciraldo said.

At the training, a small group of attendees — joined for the session by a few like-minded advocates — bonded as they fretted aloud about health emergencies for incarcerated loved ones and Justice Department findings about unconstitutional conditions at Mississippi prisons.

Butler-Smith, who said she was incarcerated for more than six years and who now lives in Memphis, was eager to learn about the lawmaking process — for example, what happens after a law is written, and how it can change.

"But I would also want to know ... the hardest thing, which is how to get in their hearts," she said of lawmakers. "How to turn them."

Butler-Smith spoke of enduring bleak prison conditions for years and challenges finding work and housing when she was released. She is interested in helping people with similar difficulties.

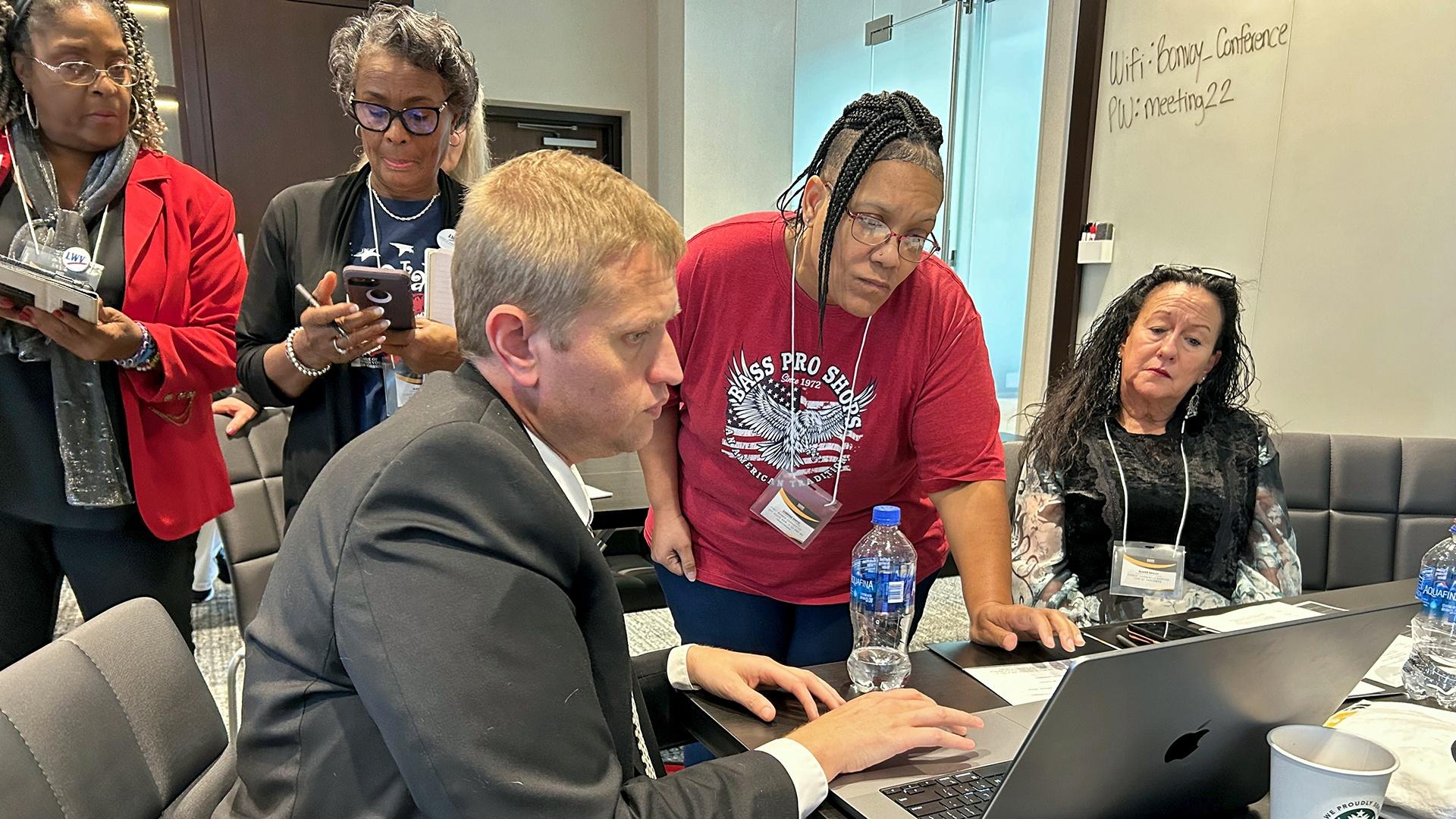

Participants hung on lobbyist LaDarion Ammons' words as he recapped the details of bills they might be interested in, including attempts to expunge some criminal records automatically.

He offered insight on some bills' authors and shared pro-tips on how best to recognize lawmakers — by signature pins often worn by House and Senate members — and warned attendees to try to keep their stories succinct.

"Use that elevator pitch," Ammons said, snapping his fingers.

Former state representative Kathy Sykes, who said her son is currently incarcerated, helped lead role-playing exercises, acting the part of a checked-out lawmaker who griped about a bill's lengthy page count.

"Anybody can be a lobbyist. Anyone and everyone," she said. "You just have to have the desire and the passion to do it."

Despite the lighthearted tone, participant Elizabeth English's hands trembled as she sat across from Sykes to practice pushing for bills.

English was attending the training, in part, to speak against Mississippi's habitual offender laws. She said those rules led to a 10-year sentence for her son over a drug case, an outcome which has devastated her family.

English's voice quivered with emotion in an interview, explaining the high cost of her son's imprisonment.

"He was not even allowed to attend his child's funeral, to touch him or to even see him one last time. So that was a harsh punishment, in and of itself," she said.

The prior year, English had visited the statehouse, but had not spoken up much, she said. With what she describes as a "G.E.D. and a G-O-D" education, she's had a lot of questions while trying to engage with legislative language.