Local journalists were also working to report information the moment they found out about it. Mark Schleifstein was a reporter at The New Orleans Times-Picayune. He stayed behind to cover the storm, losing his home in the subsequent flooding. With internet access mostly out of commission, Schleifstein and others took dictated stories over the phone from reporters in the field.

“We're covering everything that's happening in the city, and we are covering it 24-7,” Schleifstein said.

The problem, both Drew and Schleifstein said, was that their reporting was missing a key audience. Federal officials were following national TV news, but weren’t looking at reports coming from the ground. The Times-Picayune got a record of then-Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Director Michael Brown’s emails to confirm this.

“None of our reporting was showing up in his emails, which was very disconcerting,” Schleifstein said.

The federal government didn’t respond for days after the levees broke. It wasn’t until President George W. Bush’s aides showed him a compilation of news reports showing the extent of the devastation in New Orleans that the federal response changed.

By that point, national TV news coverage had also shifted. Reporters like Fox News’ Shepard Smith and CNN’s Anderson Cooper grew visibly upset on camera and called for help for the city’s residents.

Dr. Judith Sylvester, an associate professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication and author of the book, “The Media and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Lost and Found,”said that before then, there was a “political blindness” to what was happening, with federal officials attempting to downplay the destruction.

“I think it took these reporters being so angry that people began to pay attention,” Sylvester said. “It was like, ‘Whoa, why is Anderson Cooper almost on the verge of tears here? He’s so angry about this.’”

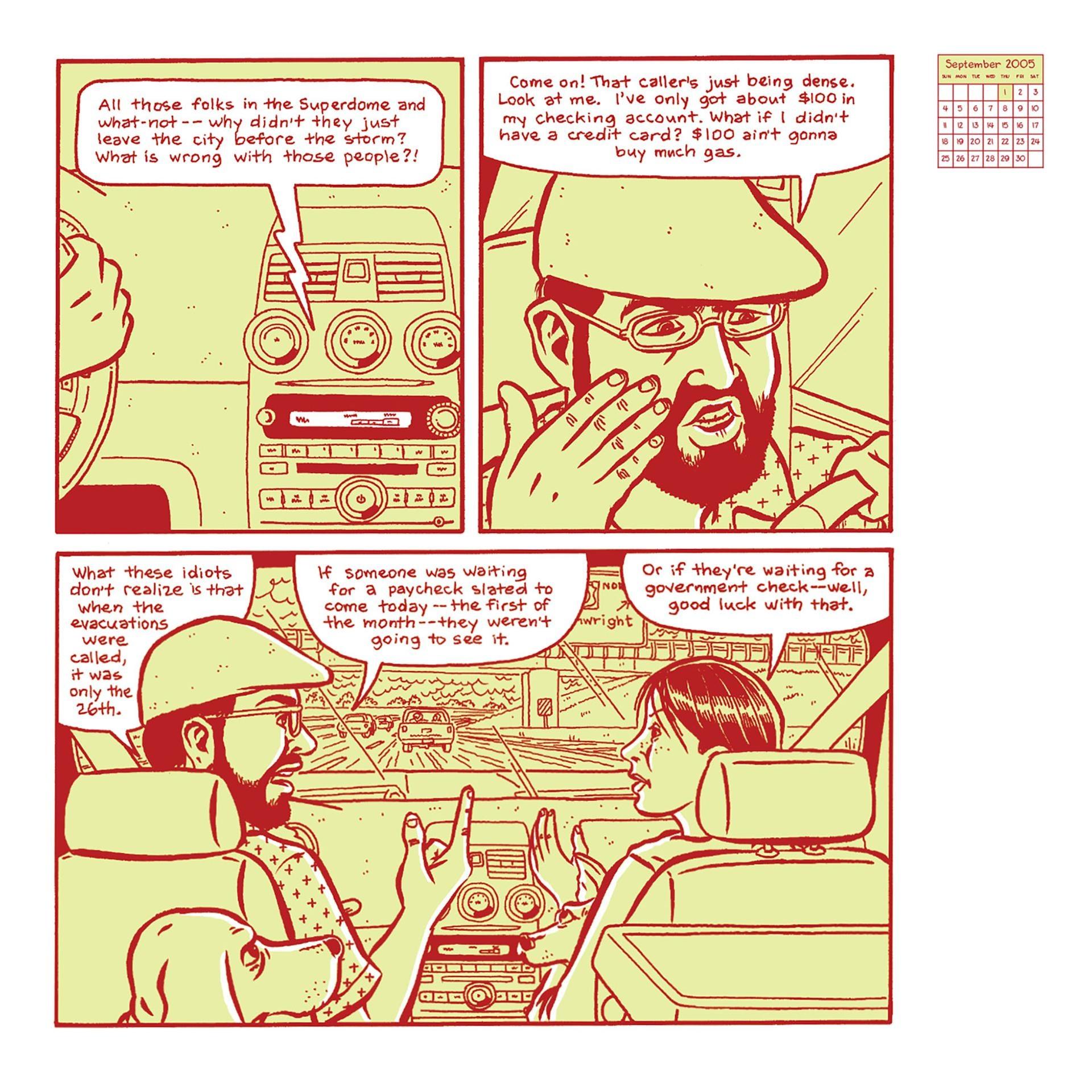

Since Katrina, that “political blindness” has gotten worse, Sylvester said, and national news is even more polarized. The loss of local publications has further contributed to the divide.

“They were the ones who were telling people in their communities. They were trusted,” Sylvester said.

In the two decades since Hurricane Katrina, more than 3,200 local publications across the country have shut down.

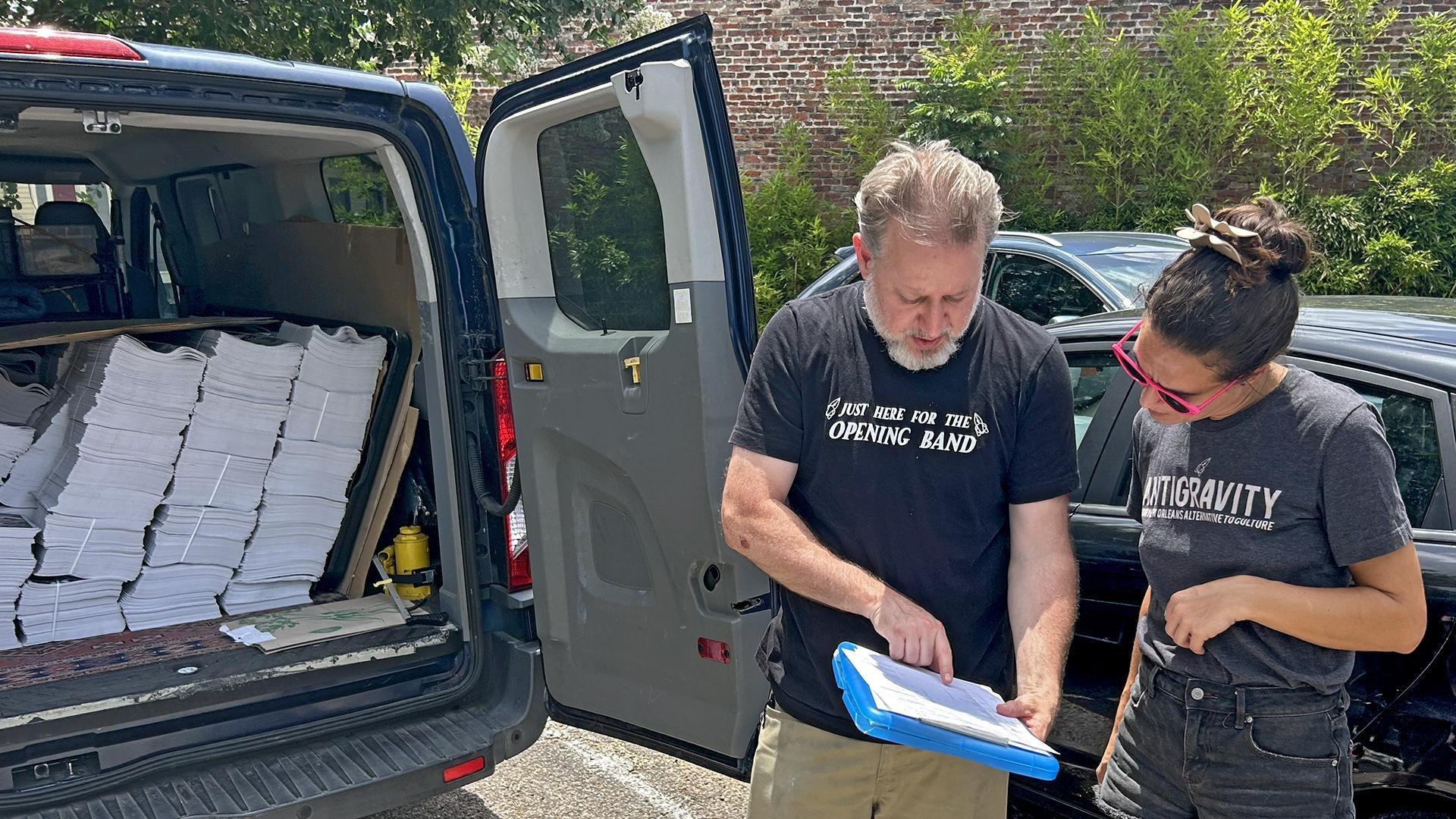

This summer, Antigravity almost became one of them. The magazine was in dire financial straits. Its ad-based model — long sustained by struggling local businesses — has been hit especially hard by New Orleans’ worsening summer slump, leaving the magazine with only a few months of fuel left.

But just like it was there for New Orleans residents after Katrina, 20 years later, the city was there for Antigravity. After a plea to readers in the July 2025 issue, the magazine saw an outpouring of support through new advertisers and subscriptions, keeping Antigravity alive.

In a note of gratitude, current editor-in-chief Dan Fox thanked everyone for their support, including local media outlets that helped spread the word.

“Thank you again, truly,” Fox wrote. “Antigravity lives to fight another day.”