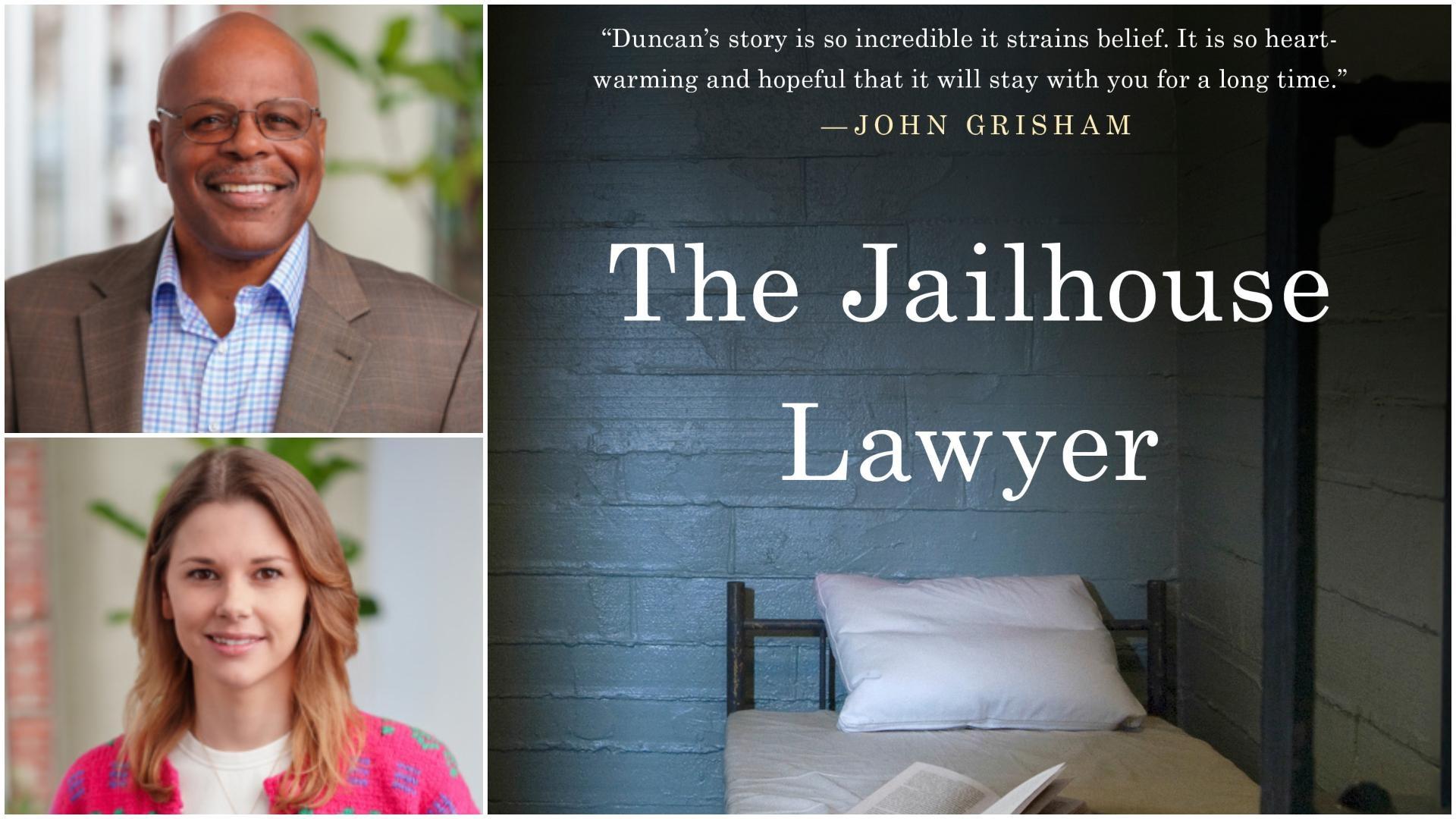

KAT STROMQUIST:

Calvin, this book details how you learned the law in prison after being wrongfully convicted. But on the way, you helped a lot of other incarcerated people as an inmate counsel or jailhouse lawyer. For people who might not know, what is a jailhouse lawyer?

CALVIN DUNCAN:A jailhouse lawyer is a person that decides to help other people [who are] incarcerated that cannot afford a lawyer, and need legal assistance in proving to the court that their convictions were unconstitutional, or filing a civil rights complaint because they are being refused medical treatment.

And most of the people that's in prison cannot afford a lawyer. So a counsel sub, or jailhouse lawyer, takes on a role as a lawyer to provide that representation.

STROMQUIST: One of the things the book talks about is the difference between a lawyer who works with clients on the outside and your work, representing the very people you were incarcerated with. Can you talk about that difference a bit?

DUNCAN: To me, the big difference is that you're in prison with the individuals, and also you're being or have been affected by the criminal justice system.

Lawyers on the outside, they are actually educated, they went to school. As opposed to us on the inside — the jailhouse lawyers — we had very little education prior to going to prison. We had no education as it relates to going to law school.

Lawyers on the outside actually went to law school and actually practice in a courthouse, whereas a person in prison, we teach ourselves the law. And I think that's the big, big distinction — that we are forced to teach ourselves to law and try to help other people.

STROMQUIST: You taught yourself the law and then you got to law school eventually, right?

DUNCAN: Yes, after I got out of prison, I went to Tulane University, where I did my undergrad. And once I graduated with a paralegal degree, I then applied to law school. And I was accepted at Lewis & Clark [Law School] in Portland, Oregon, where I got my JD.

STROMQUIST: When you guys were working on this book, you sketched in these true-to-life scenes from Louisiana's justice system across decades. You take readers from the now-shuttered House of Detention in New Orleans, to criminal court, to the prison at Angola. What did you guys do to help call up these detailed scenes from memory?

DUNCAN: Long rides to Shreveport. [laughs] Sophie and I,we both worked at the Capital Appeals Project. And we would take these long trips to Shreveport to actually consult and get with the leaders of that community, because there was a Rebel flag being flown in front of the courthouse.

And on these long trips, I would tell Sophie the stories about my journey in prison. Which was really therapeutic for me, because at that time I didn't have anybody to tell these stories to. So that's how they all came about.

STROMQUIST: Sophie, what was it like hearing those stories?

SOPHIECULL: Calvin is a true storyteller in the tradition of Southern storytelling. He provided so many of the rich details that make up the scenes in the book, and so listening to him, it was like watching a movie on those car rides.

It was incredible to hear not just what he'd been through, and what he had done with his time in prison, but to have him take me inside those walls and really share scenes of his life was remarkable. And I think because I have my own experience in some of those places it also helped me to be able to paint a picture with Calvin of some of those scenes from being in the courtrooms and visiting Angola in my professional life.