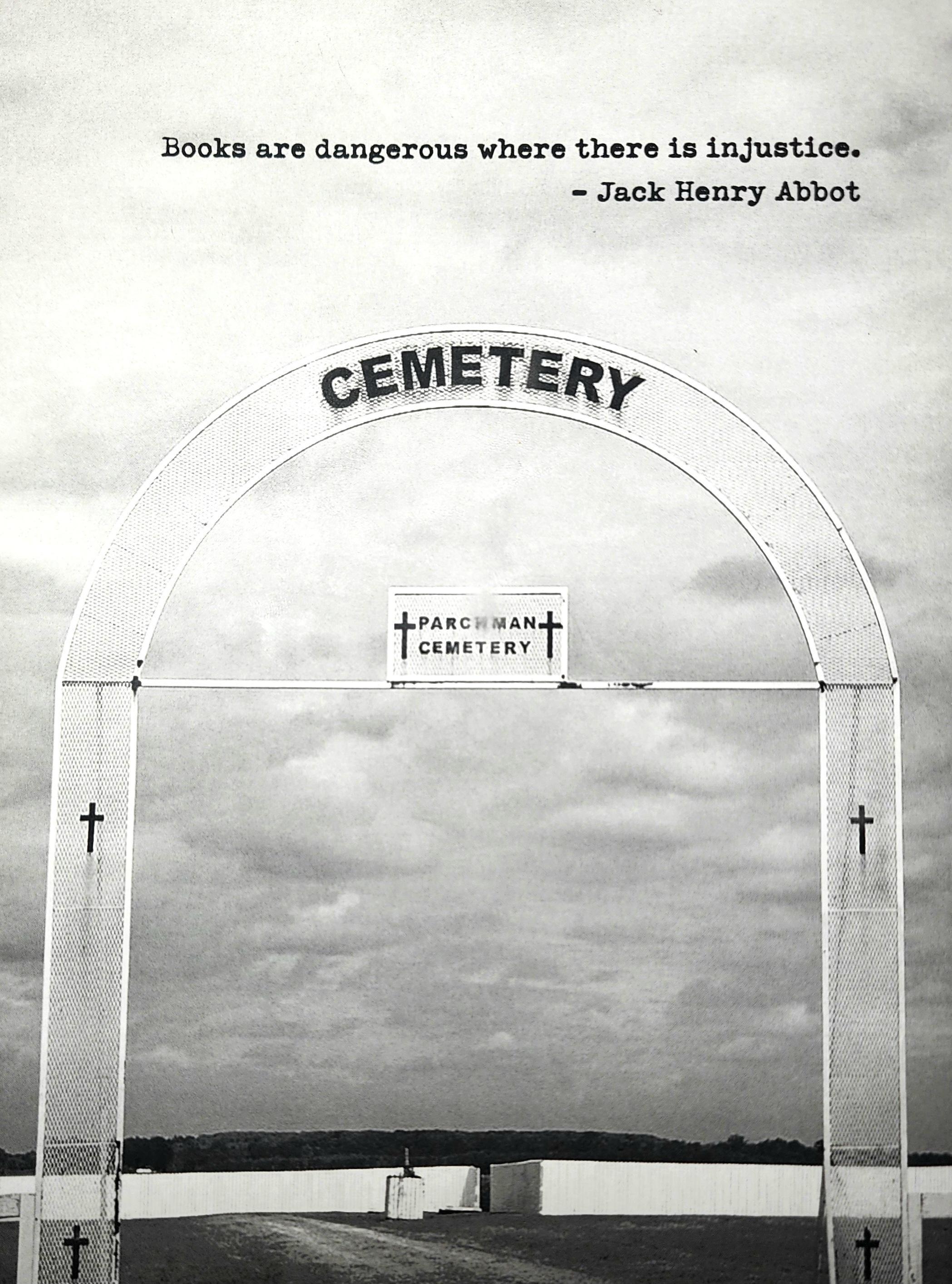

The conditions at Parchman, ranging from cruel forms of corporal punishment, deteriorating conditions and racial segregation, have been notorious for decades beyond the sprawling, flatland Delta that it comprises.

In the early 1970’s, only years after hundreds of Freedom Riders were interred at the prison, four men incarcerated at Parchman filed a federal, class action lawsuit alleging that conditions deprived them of their First, Eighth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendment rights.

The suit, Gates v. Collier, focused on the facility’s use of the so-called ‘Trusty System,’ wherein men serving life sentences – many of them for murder – were provided with rifles by officials, and the responsibility to mete out punishment and oversee men who worked under them at the prison’s many dispersed labor camps.

The state government at the time justified their reliance on this system, and the myriad abuses and deaths which it produced, as a way to reduce the facility’s annual budget. In return, those labor camps produced hundreds of thousands, and later millions, of dollars for the state’s budget.

After the lawsuit was filed, federal judge William Keady for the Northern District Court of Mississippi visited Parchman on numerous occasions, noting its resemblance to conditions under American slavery: 100-120 men sleeping in a single, run-down room, open ditches of raw sewage and medical waste, frequent murders and beatings and the use of its maximum security unit as a torture chamber.

Years later, after the state of Mississippi appealed Keady’s ruling that Parchman must end all unconstitutional practices immediately, the regional Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed his decision.

In effect, Gates v. Collier not only ended the use of the Trusty system in Mississippi, but also in neighboring Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana and Texas. It also marked the first broad-scale intervention by a court in the supervision of prison practices.

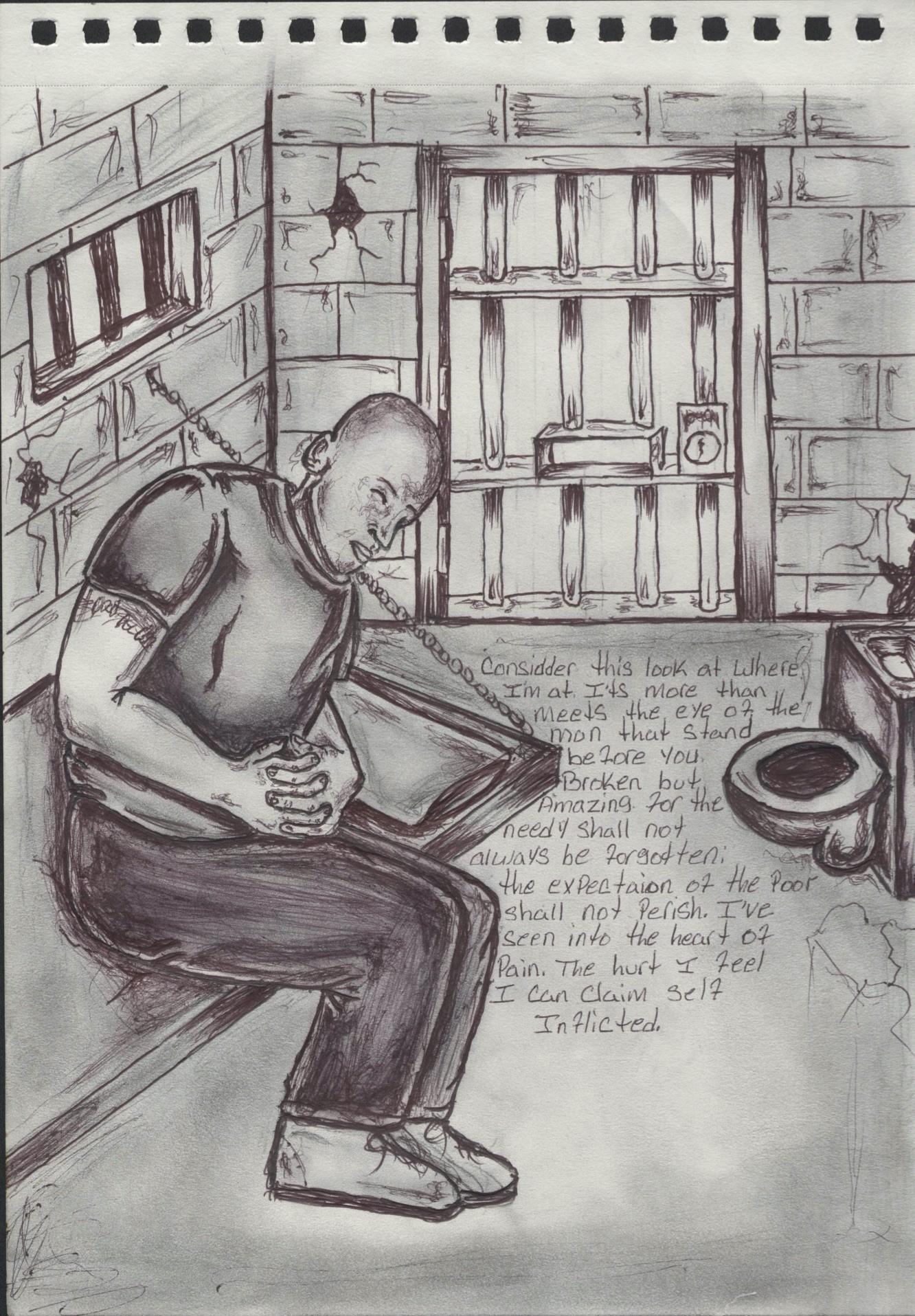

But an essay included in the book, authored by current ‘lifer’ Rufus McFadden titled Know Your Job, shows many of the same issues persist in Unit 29 today:

I had started brushing my teeth as I walked toward the bathroom area. I had to walk around several people as they scrimmaged throughout the pod. There was so much smoke in the air and the noise was like it was noon time instead of early morning. The pod was still filthy from the day before. I eased past the crowd and made it to the sink.

As I brushed, I noticed a sudden quietness. The quietness brought about an eeriness inside me as if something very bad was about to happen; the hairs on my arms stood at attention and a violent chill coursed throughout the vicinity in which I stood. Everything in my soul was telling me not to look back.

Then I slowly looked back. The scene was like it was being played out in slow motion. I'll never forget the sound of wood smashing flesh and hitting bone. The officer had coerced three inmates to assault a guy seeking a legal assistant form. She sat back and watched while the inmate was almost beaten to death. I'll never forget the wicked smirk that was displayed upon her face. I could feel her madness as she enjoyed the brutal beating…

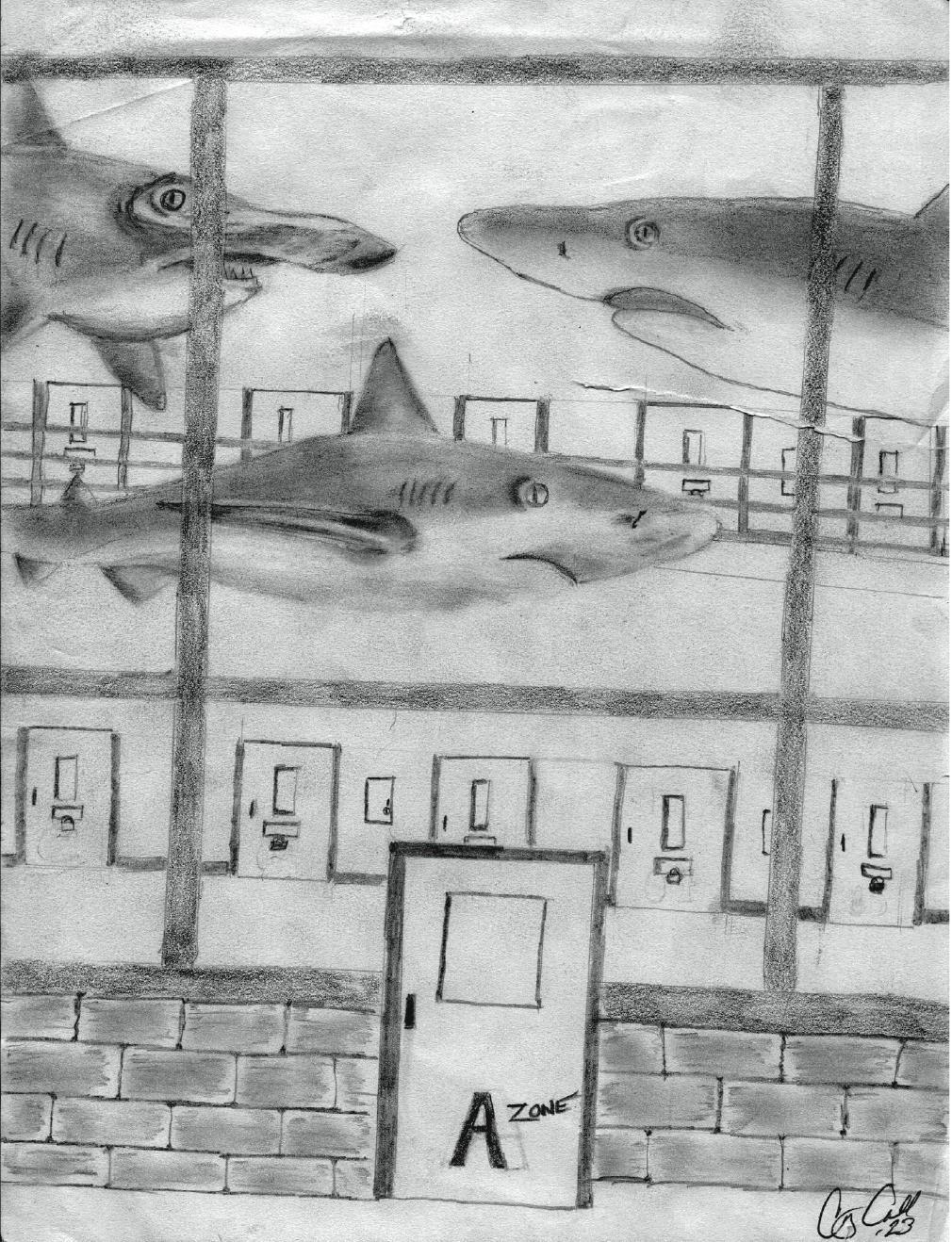

In this essay, McFadden is describing one of many systemic issues outlined in a 2022 Department of Justice report, which found that amid severe understaffing at Parchman, those incarcerated on Unit 29 are subject to an environment rife with weapons, drugs, gang activity, extortion and violence.

That same Department of Justice report found numerous violations of both Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment protections, including that in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, those in Unit 29 don't even have air conditioning.

The investigation which produced those findings was launched in February 2020, shortly after the gang violence and rash of suicides that broke out at Parchman, and outcry from hundreds of Mississippians who demonstrated in front of the state capitol building demanding reform.

Only months prior, in his first State of the State address, Gov. Tate Reeves said he’d begun instructing Mississippi Department of Corrections officials to shut down Unit 29 for good after touring it personally, later describing it as the ‘tip of the spear’ of Mississippi prison violence.

Between 2014 and 2020, according to comparisons of annual MDOC budgets filed by the Joint Legislative Budget Committee, Mississippi lawmakers cut the corrections department’s budget by a combined total of $215 million.

“There are many logistical questions that need to be answered…but I have seen enough. We have to turn the page. This is the first step, and I have asked the Department to begin the preparations to make it happen safely, justly, and quickly,” Reeves said from the steps of the Capitol building.

“I know that we will make progress day by day. It will often be slow, it will often be painful, as we reckon with the mistakes of the past. We will learn from them… we will do better, and work together, to ensure that the safety and dignity of all Mississippians are [sic] respected.”

But today, the near-mythic Unit 29 remains open despite that pledge.

During the 2024 state legislative session, Senate Corrections committee chair Juan Barnett, D-Heidelberg, filed a bill that would have phased down the operation of Parchman in its entirety over a four year period, transferring men incarcerated there to a few nearby facilities. But that effort died before even being put to a vote.

For Rufus McFadden and hundreds of other men in Unit 29, that means daily life inside the zone’s brutal walls, and amid its unsanitary conditions, only continues.

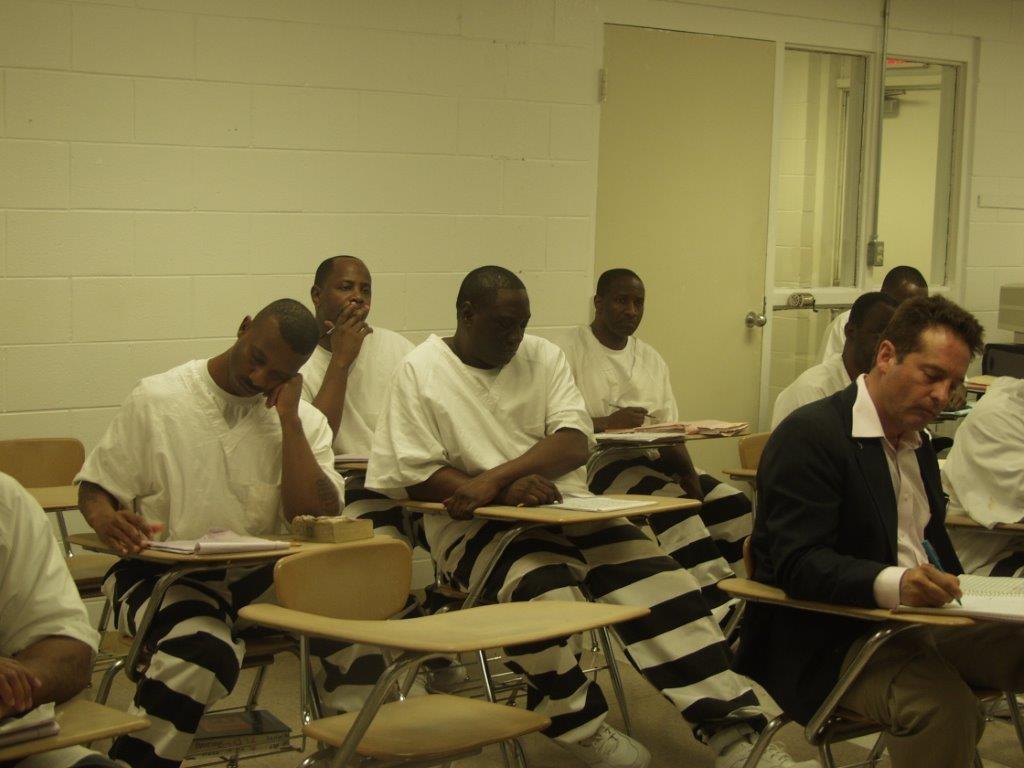

At Vox Press, the work to compile Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison – the publishing house’s fourth book of Mississippi prison writing – presented Louis Bourgeois with an existential question of his own:

“We've done good work, but what are you trying to achieve now? What I wanted to achieve with this book was no kind of censorship, really. This is an extreme situation; what now can this book purport to do, but for society to receive a message that it needs to receive and then question what all this is about?”

“We all grew up in English departments where writing is almost a luxury thing, or to get tenured. But this one of the few situations where writing actually has almost a matter of life or death thing to it. To them, this was like a last chance to get an utterance heard. It's real stuff, and for some of these guys, it's everything. They put everything into it – what more could you want from a student, from a writer?”