“We have to put our money where our mouth is when it comes to those things,” said Brandon del Pozo, a public health and justice expert at Brown University and a former police chief. He pointed to the "failure" of Oregon’s attempt to decriminalize drugs in 2021.

The law removed criminal penalties and aimed to connect people to voluntary treatment. But few sought help, overdose deaths soared and public disorder worsened.

The state has since reversed course, reinstating criminal penalties. Del Pozo said effective drug policy has to balance public health and criminal justice.

“It's not just about a change in the law. It's about properly funding meaningful public health alternatives, which they've done in a lot of Europe,” del Pozo said. “We haven't put the funding and those resources in place here. And then when it fails, we say it was a terrible idea, and we don't want to try it again.”

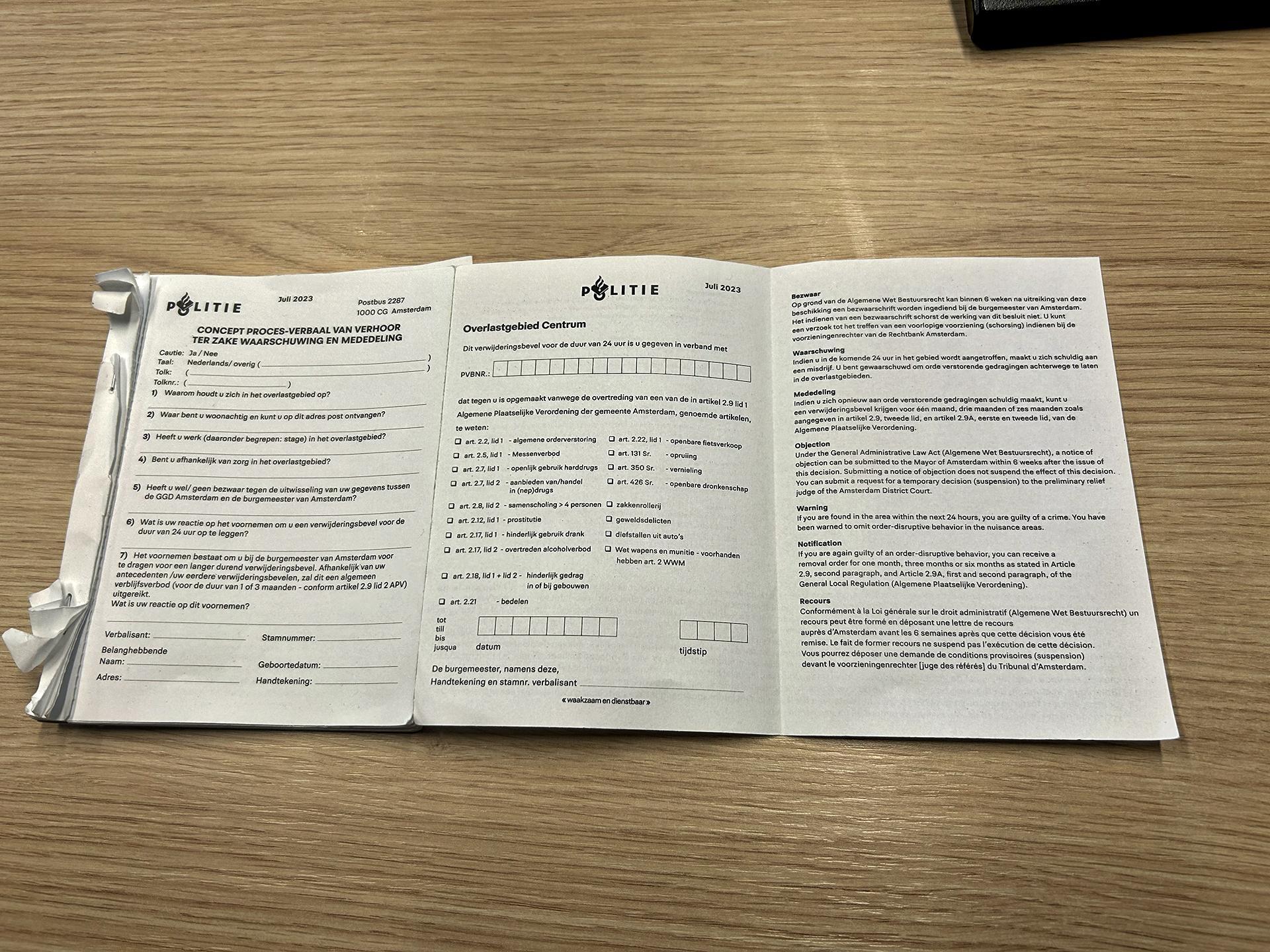

Police in the Netherlands also don’t have to contend with guns like American police do. They’re illegal in the Netherlands without a special permit for shooting sports and hunting. In the U.S., there are more guns than people.

“Every time the police have an encounter with an unknown person who may be acting a little erratic, the worry that they have a gun is top of mind,” del Pozo said. “And that is not paranoia. That is working as a cop in a country with 400 million guns. So that is a big difference.”

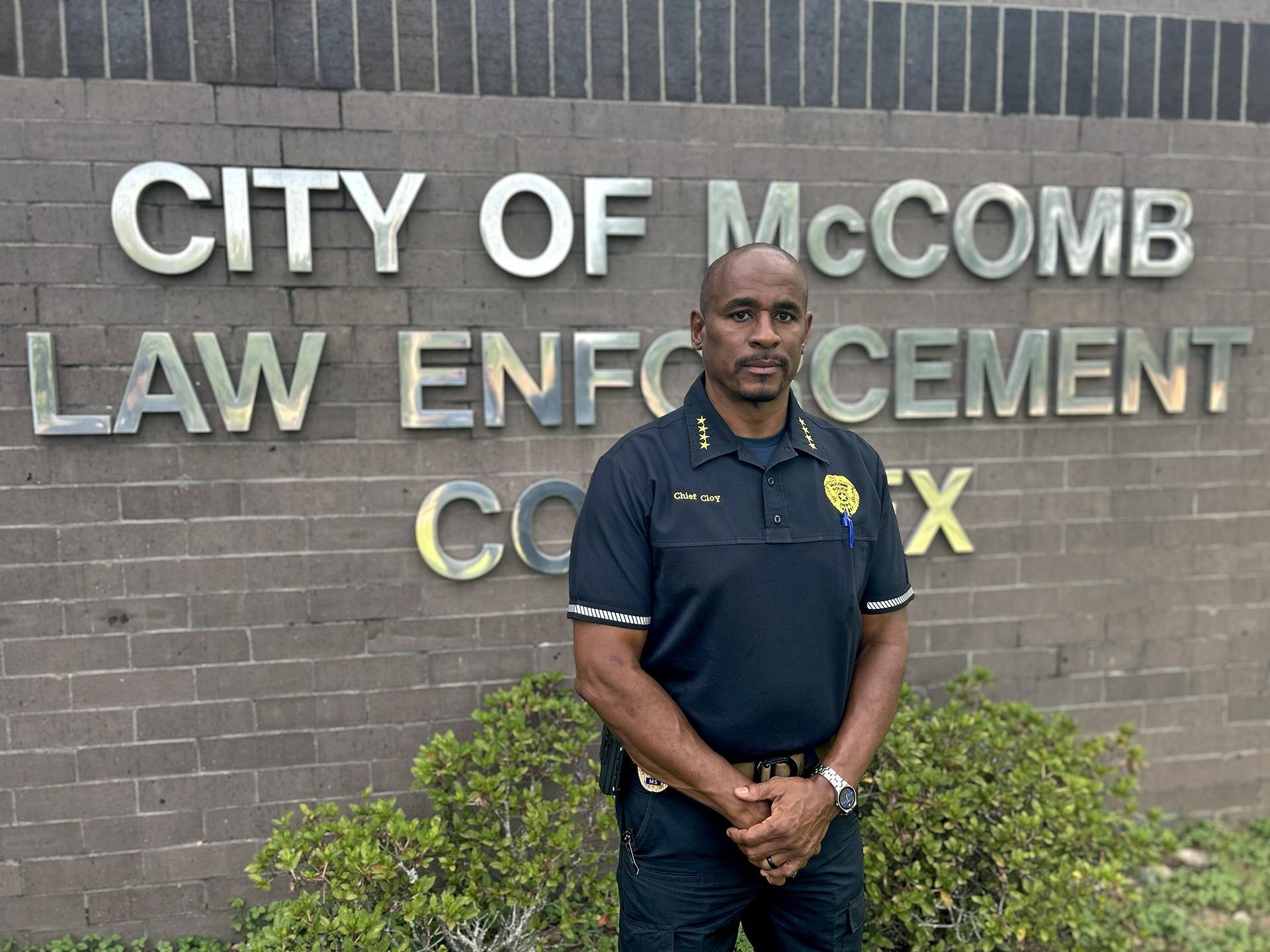

Local context also matters. Cloy said he recognizes the pushback harm reduction and a public health approach faces in states like Mississippi.

But the broader, American cultural view of drugs is part of the problem, too. Cloy describes an “it’s not me that’s hurt, it’s you” mindset that positions drug addiction as an individual, moral failure rather than a medical problem that impacts the entire community.

Unless that changes, “We’re going to always have opioid epidemics,” he said. “And it’s still going to fall on law enforcement.”

Cloy is comfortable sharing his views on harm reduction with other departments in training sessions, but he stops short of suggesting drug use be legal.

"We're not like the Netherlands. The Netherlands are the Netherlands," Cloy said. “Just being able to really consume that and get my mind wrapped around that thought process totally, it’s a very difficult thing to do.”

One of Cloy’s officers, Tyler Harvey, who volunteered to drive the mobile unit distributing naloxone, echoed this sentiment in a thick, Southern Mississippi accent.

"This is harder to wrap your head around from our eyes... the families it ruins, the lives it affects, the lives it takes," Harvey said. "To see it legalized. It's just hard to grasp."

Cloy, Harvey, and del Pozo said most police feel the criminal justice approach is ineffective and damaging. But every year, nearly a million people are arrested for drugs across the country. And despite recent reductions in overdose deaths, the number of people dying in the opioid crisis is still at “catastrophic” levels.

“What we're doing, I haven't noticed it work. Nothing's really stopped it,” Harvey said. “A radical shift might work, it might not work. Like the chief just said, we're a different culture.”