“Being infertile is just, it's invisible,” she said. “People can't see it, except that they don't see a child.”

Lynn went through 24 rounds of artificial insemination. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, around 13% of women aged 15 - 49 in the U.S. experience difficulty getting pregnant. Lynn’s husband, Dick, says the threat of infertility was traumatic.

“You wait to the end of the cycle, hoping that you're pregnant and then if it doesn't work out then, you just cry,” he said, his voice breaking.

Still, in 1984, the couple felt a glimmer of hope.

While attending an infertility support group, they became aware of a new treatment at the University of Mississippi Medical Center: in-vitro fertilization, popularly known as IVF.

The IVF program was the first in the state and one of the first in the nation. Founder Dr. Bryan Cowan created the program at UMMC in 1983.

The Lawrences decided to be one of the first families to participate.

“I still remember the first time I went in for IVF, for my first appointment, where we had gone through the pre -check period where they evaluate you and make sure that you're qualified, that you are a good candidate for it,” Lynn said. “I met all the criteria. I didn't have anything that couldn't be overcome. I had several problems, but it wasn't anything that was insurmountable.”

IVF is a procedure that involves removing eggs from a woman's ovaries. The eggs are then fertilized outside of the woman’s body. If the resulting embryos reach a certain stage of development, they are transferred into a woman's uterus with the hope that it results in a pregnancy.

“It was a neat time to be our age to be of childbearing, those years,” Lynn said. “On the cusp of such a huge frontier that was, I mean, it had just arrived into Mississippi. It was just arriving in the South. It was everything. So much in medicine was changing then. It was an exciting time to get pregnant.”

The Lawrence’s were told only three eggs could be retrieved from Lynn at a time.

“I didn't think emotionally I could handle more than two, which was probably true,” she said.

Lynn says she went through the lengthy IVF process twice. Neither worked.

“We didn't want to hope because we knew that the odds are not in your favor for the first time, but it still hurt” she said. “So we planted some dogwood trees in our yard. We did that again for the second procedure too.”

Dr. John Rushing is the current director of the IVF program at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

“The first thing I like to tell patients is that I have infertility myself and that's ultimately why I got into this field,” he said. “I knew the emotions of what those patients were going through because I had been through them personally with me and my wife. We required IVF for treatments.”

He says in the ‘80s, IVF only had a 20 to 30% success rate. Now, after vast improvements in IVF medications, Rushing says patients can expect 60 to 70% success rates in IVF treatments. He emphasizes, though, that it’s not possible to know exactly how many embryos each person will create or if they will be viable.

“Not all that do fertilize will make it to an embryo stage,” Rushing said. “Also, not all embryos will be capable of life.”

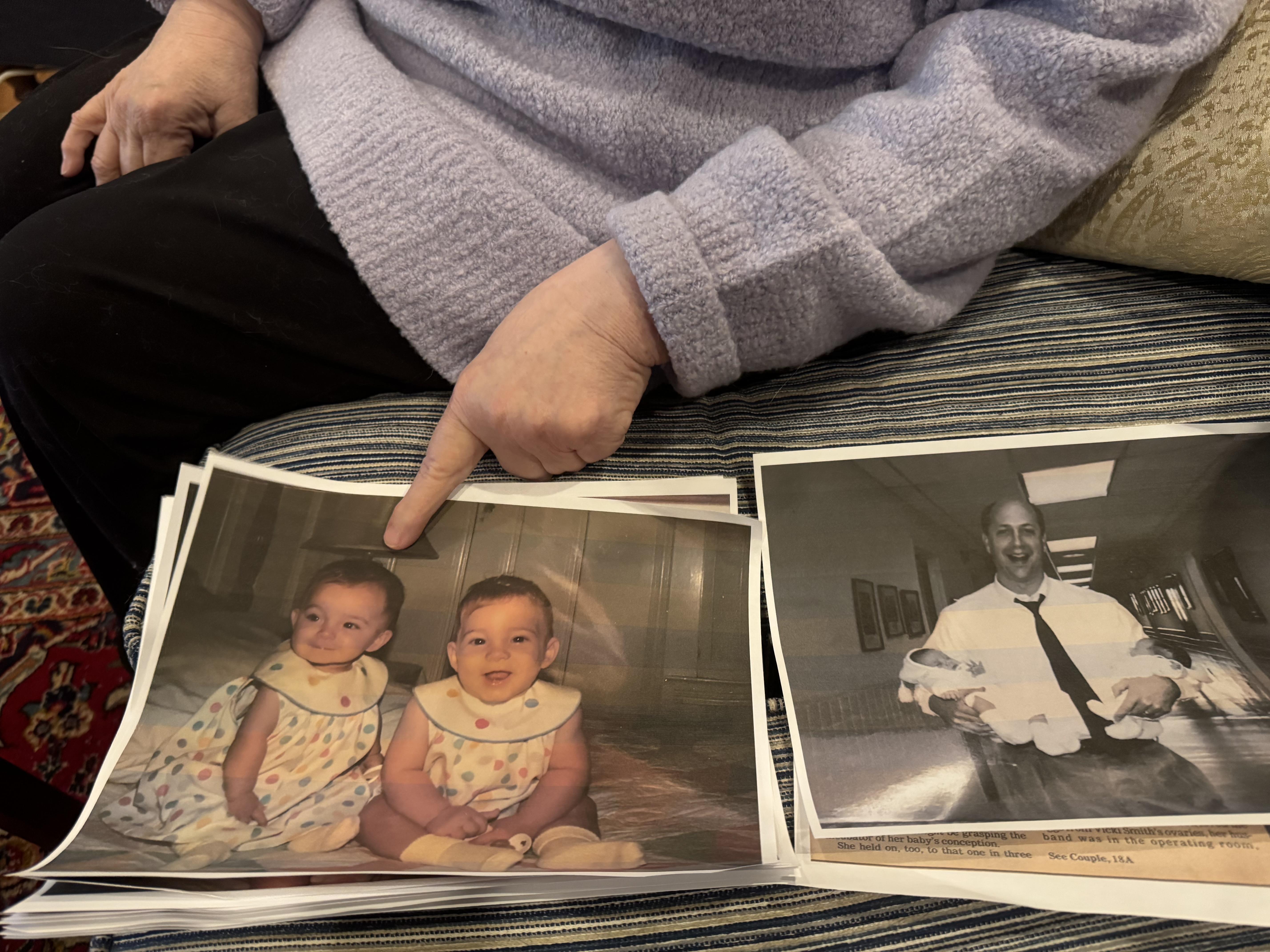

Rushing says the first Mississippi IVF baby was born in 1984 through the medical center's program. The following year, Dick and Lynn Lawrence went through their third round of IVF treatment at UMMC. Ten days later, Lynn went back to the doctor.