Till’s story has been told before, and there are details that are pretty widely known. Till was 14 years old when he was lynched by two white men while he was on a trip to visit family in Mississippi’s Delta region in 1955. After his death, his mother had to fight to make sure people knew what happened to her son, so she insisted on an open-casket funeral.

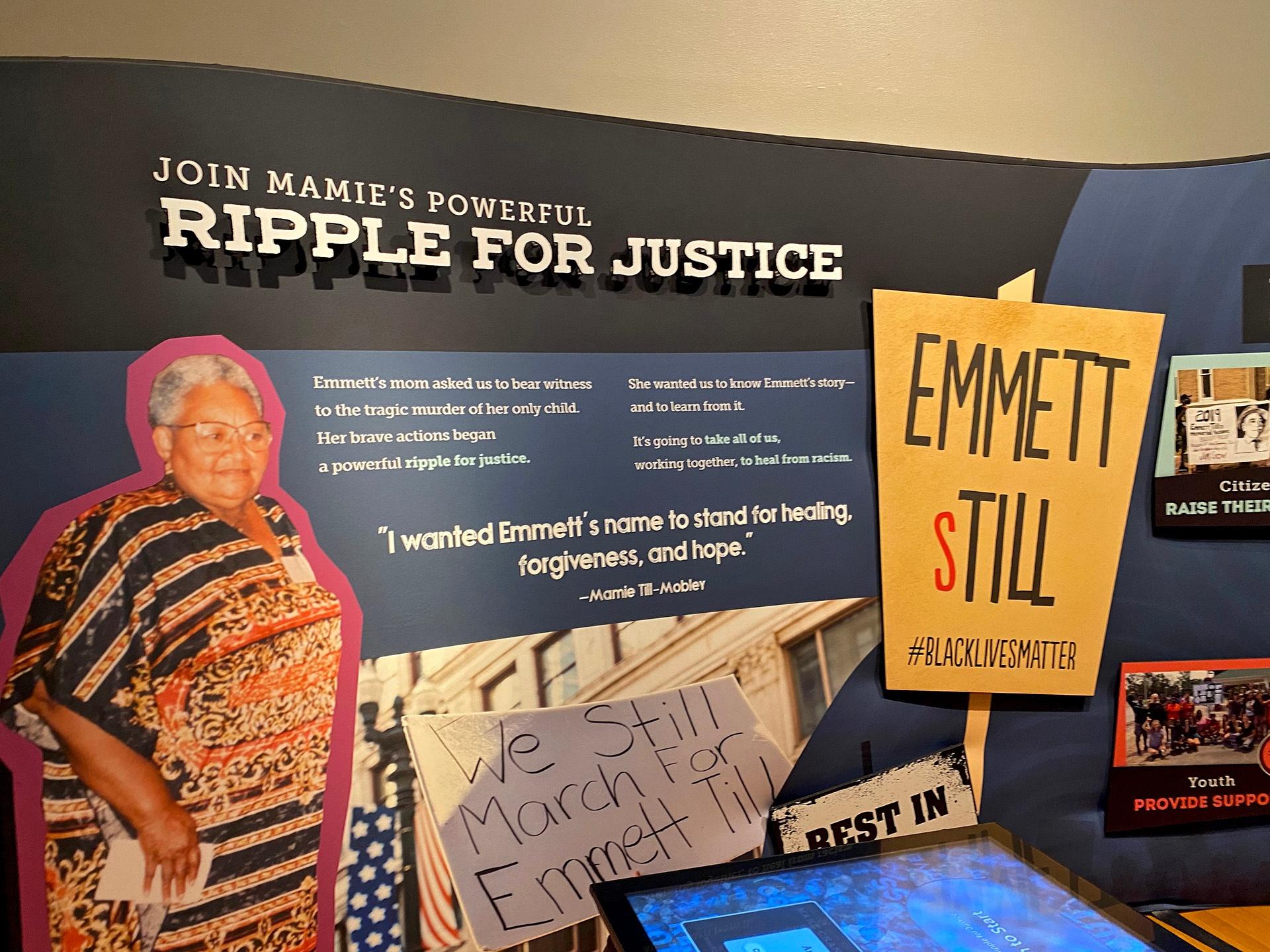

Now, a new exhibit at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute dives deeper into what happened after he died. Mamie Till Mobley didn’t fade into the background. She became a civil rights activist whose work continued long after Till’s funeral.

“What we like to say is that we’re so excited that Hollywood has picked up this story. But our job is really to allow people to go deeper,” said Patrick Weems, the executive director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center — which is based in Sumner, Mississippi.

For over a decade, the center has worked to keep Till’s story alive. That’s why it recently partnered with the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis to create the traveling exhibit — ”Emmett and Mamie Till Mobley: Let the World See.” The museum reached out to the center to collaborate after a marker commemorating Till’s death was desecrated with bullet holes in 2019. Three University of Mississippi students took a photograph while posing next to the damaged sign and holding guns, but denied shooting it.

“They saw this picture of students standing with guns in front of that sign. And they reached out to me to say, you know, what could we do and what do y’all do with those signs?” Weems said.

That same marker, among other artifacts, like letters from Mamie Till Mobley and newspapers from that time period, are safely preserved in the interactive exhibit. It also includes a short documentary video for visitors to watch.

The archival photos and videos affected a lot of people that visited the exhibit recently, including local activist Sherrette “Lady Freedom” Spicer, who cried as she talked about her experience with it.

“Even though it’s something that is hard to see, it’s also hard to live and be black,” Spicer said. “It’s really an encouragement to just keep fighting for justice and to keep telling the truths about what happens to us.”

Zoe Smith, a teenager who went to the exhibit with her family, said getting a deeper look at what Till went through was upsetting.

“I felt very angry because … no person should go through that type of thing,” Smith said. “I just feel like if I ever went through that, I would be upset, mad. I couldn’t control it.”

During its most recent stop in Birmingham, the exhibit celebrated its opening with a special program at the 16th Street Baptist Church — an important landmark in the civil rights movement, itself — that featured a musical performance, spoken word, and guest speakers.

Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., Till’s cousin and the last living person to witness Till’s abduction, was one of those speakers. He told the packed crowd about the last time he ever saw his cousin and the importance of keeping his memory alive.

“I always preface the story like this. This is an American story, but it’s not a pretty story. It’s not pleasant,” Parker said.