Black communities in the Gulf South have long grappled with contamination — whether in their water or the air they breathe.

In the fight for environmental justice, Birmingham tells Jackson to stay loud

Black communities in the Gulf South have long grappled with contamination — whether in their water or the air they breathe.

Gulf States Newsroom

In the fight for environmental justice, Birmingham tells Jackson to stay loud

Jackson, Mississippi and Birmingham, Alabama are two predominantly Black cities that have seen similar consequences after years of pollution. Residents of both have spent years working towards solutions in their own communities. Now, the two cities are trying to use their experiences to advocate for continued awareness.

Jackson is home for Terun Moore. Late August, his city experienced a water crisis that left all of its residents without clean drinking water. The aftermath highlighted Jackson’s chronic issues with low water pressure, contaminated water and failing infrastructure. On top of that, the city is also grappling with hundreds of lead contamination claims over the last year.

For his whole life, Moore accepted Jackson residents boiling their water as normal. But he’s ready for that to change. As a member of the Mississippi Rapid Response Coalition, he’s been helping distribute clean water to residents since August.

“It’s been harming us for years,” Moore said. “And you wonder why violence is up. You wonder why these people are acting like that. We raise the kids with contaminated water in a food desert.”

Tariq Abdul-Tawwab, another Coalition member, spent several months answering the mayor’s action line. During that time, he said Jackson residents have told him, in great detail, about their everyday worries. He’s heard them talk about not being able to give their children breakfast, about not brushing their teeth for days or their worries of smelling because they have to bathe with bottled water.

Abdul-Tawwab said this problem isn’t new – it has roots in the Reconstruction era.

“Mississippi, historically, has denied African-Americans and the descendants of slavery rights to anything they can,” Abdul-Tawwab said. “That’s the reality that we’re in.”

The Mississippi Rapid Response Coalition has rallied with other groups each month in front of the governor’s mansion and state capitol to pressure state officials to fully fund a solution. It all shows how Jackson residents are taking care of each other.

“Until our government step up, we’re just going to step up,” Moore said.

At a November Poor People’s Campaign rally, residents shared stories of becoming sick, having children with birth defects and even dying because of the contaminated water.

Among key demands has been keeping the water system public and in the City of Jackson’s control. For the next year, the U.S. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Environmental Protection Agency will play a direct hand in improving the city’s water system as part of an agreement with the City of Jackson. The DOJ appointed manager Ted Henifin, following a federal judge’s approval for the intervention.

Grappling with systemic barriers is also the fight the residents of north Birmingham in Alabama face. The majority Black area has experienced over a century of exposure to coal plants that have polluted the air and soil.

“Environmental pollution has been a chronic albatross in African-American communities and communities of color for generations,” said resident Marcia Forrest.

Tammie Smith, 59, said she firmly believes the pollution from the nearby plants have caused illnesses on a massive level. She’s watched family and friends succumb to breathing problems and cancer.

Like Moore, Smith said for most of her life, she was used to it. She comes from an underserved area.

“Where we were living, we couldn’t afford to pack up and go,” Smith said.

As she’s gotten older, she’s become more aware of how pollution has impacted north Birmingham and finding a solution.

Smith and Forrest shared their stories during a monthly meeting for People Against Neighborhood Industrial Contamination, or PANIC.

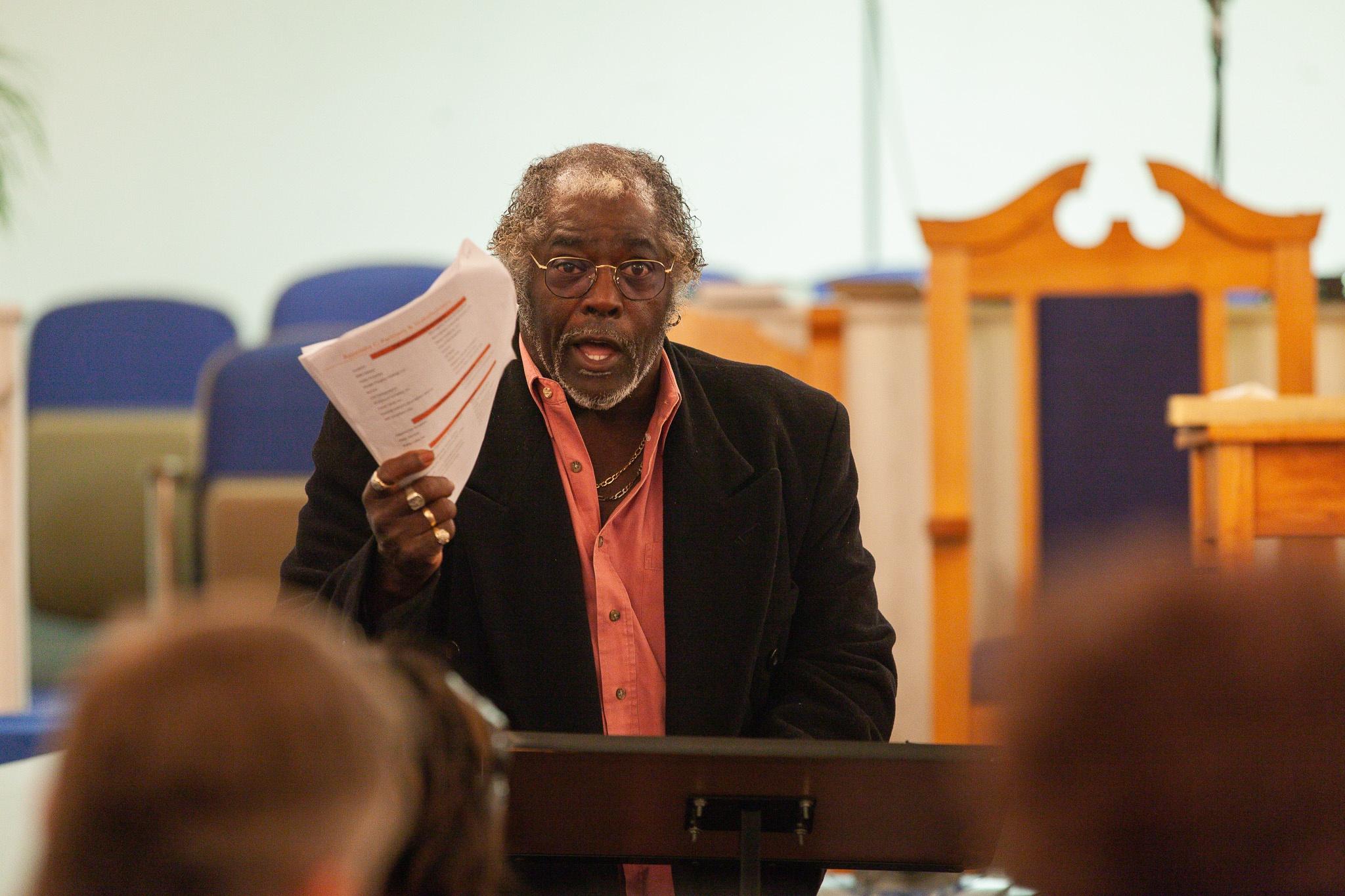

Charlie Powell started PANIC over a decade ago. He was called to action after a community meeting with Lois Gibbs, referred to as “the Mother of the Superfund” for her work exposing toxic waste. Portions of north Birmingham are considered a Superfund site, meaning it’s a contaminated site identified by the EPA for cleanup.

Powell organizes for the people he’s lost over the years. Once, his daughter pointed out how he quit drinking – and swiftly pointed out the reason was because all his drinking buddies were dead.

“We used to sit down and drink, having a good time, but they ain’t here no more,” Powell said. “And this is why I’m doing this for my buddies, or what you say, my homies.”

Like Abdul-Tawwab in Jackson, Powell points to a long history of discrimination. The air pollution mostly hurts historically Black neighborhoods in Birmingham where people were forced to live due to redlining.

“You got to always remember that Black folks always had a limited amount of places they could stay and that was going to be always around plants and all of that,” Powell said.

Birmingham residents have learned some lessons over the years that they think could help their neighbors in Jackson.

For one, PANIC hosts monthly neighborhood meetings. This way they can keep everyone informed about what’s going on, address rumors, and support one another.

Amanda Doctor was unaware of the reason behind the rotten smell in the air until her neighbors explained. She eventually ran across one of Powell’s fliers and learned more about the issue.

PANIC has been pushing federal and local leaders for years to shut down the plants and pay residents to relocate or compensate them if they stay. After a decade, Powell feels closer to relocation now more than ever.

Bluestone Coke, one of the plants PANIC wants to see remain shut down, was fined in December over $900,000 after years of violating its air pollution permit. It was a move made by the environmental justice group the Greater-Birmingham Alliance to Stop Pollution, the Southern Environmental Law Center and the Jefferson County Department of Health.

“Only thing I want is Bluestone Coke, hey, do what’s right for everybody. I mean, real talk, do what’s right. Help move these people from around here. If you’re going to open up or do whatever, move people from around here because y’all are really messing us up,” Doctor said.

And they say it’s important to stay loud. Smith said it’s important to keep pressing the issue and use all the platforms they can to voice their opinion because “they don’t want to hear you.”

“They don’t want the world to know that they’re not doing the thing that they’re supposed to do,” Smith said.

And, finally, they say ‘do your own research.’ The city of Birmingham came out with “the Big Ask,” a draft planthat could put millions into a buyout program. Powell argues that it’s not enough. So, PANIC is going door-to-door in neighborhoods around the coal plants, and surveying residents about what their homes are actually worth.

The Gulf States Newsroom’s Taylor Washington and Mississippi Public Broadcasting’s Lacey Alexander contributed to this story.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.